You can access the distribution details by navigating to My Print Books(POD) > Distribution

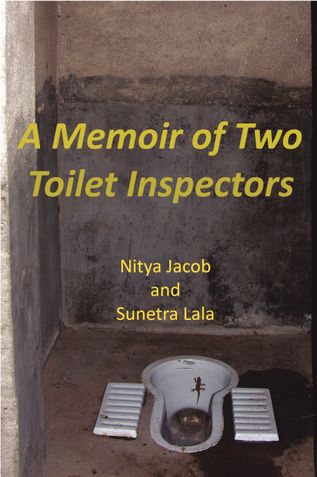

Description

India has witnessed the world's largest behaviour change programme, as the mandarins of the country's sanitation programme called it. From 2014 to 2019, more than 100 million toilets were made. The government paid for these and a myriad of people toiled for the toilets. There are stories of sacrifice and valour as in any military mission. Only, making toilets is not a conquest. It is a change in the way of life for hundreds of millions living a perilous rural existence. Toilets competed with their priorities for food, water and jobs. In the building frenzy, a dark comedy emerged.

The frenzy unleashed an army of experts, an avalanche of money and a winner-takes-it-all method. In what followed, history repeated itself. India has run none-too-successful programmes to provide toilets for people since the 1950s. In 1999, the paradigm changed. From being a government benefactor-led programme, it became demand-led. People were to be convinced to make toilets by skilled motivators. They would apply to the government, get a subsidy and put in their own money to make one. Progress crawled, as the authors have documented, from 1999 to 2014.

The toilet-tango continued through successive avatars - the Total Sanitation Campaign became the Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan in 2012. And the Swachh Bharat Mission in 2014. Recording changes in the decade from 2007 to 2017, through interviews and observations across seven states and about 20 districts, the authors aver the more things changed, the more they remained the same. The government made people build toilets and paid out subsidies in 2007. They continued doing so in 2017, but insisted these were termed incentives, not subsidies. The pay out in 2017 was 10 times that in 2007. A powerful motivator, the writers found.

While they were out making toilets on the frontlines with the trained motivators (swachhagrahis), they forgot to tell people how to use them. And why they should do so. Whilst villages, districts, states and eventually the whole country was declared ODF, meaning every listed house had a toilet on paper, in reality the authors saw the universal programme had in places passed over the poor and excluded. It was so earlier; it was repeated in 2017.

There was an absurd wall painting in a village of a backward state. It showed a gangster making off with a woman who had gone to the fields to defecate. In 2007 as also a decade later, women bore the brunt. The lack of toilets forced them to go out to answer nature's call. The motivators insisted toilets were the gateway to safety and dignity. It became a woman's problem, not a societal one. The book is a qualitative travelogue of the sanitation journey of these states. It documents the similarities and disparities in approaches, actors, results, problems, solutions, institutions, agents of persuasion and change. It explores India’s tryst with toilets - its beauty spots and warts.

About the Authors

Book Details

Ratings & Reviews

Currently there are no reviews available for this book.

Be the first one to write a review for the book A Memior of Two Toilet Inspectors.

Other Books in Politics & Society, Travel

ಕಿರಣ್

Alex Andelonard

Krishnendu Santra

Art Saguinsin